Note

Click here to download the full example code

Plotting data points¶

GMT shines when it comes to plotting data on a map. We can use some sample data that is

packaged with GMT to try this out. PyGMT provides access to these datasets through the

pygmt.datasets package. If you don’t have the data files already, they are

automatically downloaded and saved to a cache directory the first time you use them

(usually ~/.gmt/cache).

Note

This tutorial assumes the use of a Python notebook, such as IPython or Jupyter Notebook.

To see the figures while using a Python script instead, use

fig.show(method="external") to display the figure in the default PDF viewer.

To save the figure, use fig.savefig("figname.pdf") where "figname.pdf"

is the desired name and file extension for the saved figure.

import pygmt

For example, let’s load the sample dataset of tsunami generating earthquakes around

Japan (pygmt.datasets.load_japan_quakes). The data is loaded as a

pandas.DataFrame.

data = pygmt.datasets.load_japan_quakes()

# Set the region for the plot to be slightly larger than the data bounds.

region = [

data.longitude.min() - 1,

data.longitude.max() + 1,

data.latitude.min() - 1,

data.latitude.max() + 1,

]

print(region)

print(data.head())

Out:

gmtwhich [NOTICE]: -> Download cache file: @tut_quakes.ngdc

[131.29, 150.89, 34.02, 50.77]

year month day latitude longitude depth_km magnitude

0 1987 1 4 49.77 149.29 489 4.1

1 1987 1 9 39.90 141.68 67 6.8

2 1987 1 9 39.82 141.64 84 4.0

3 1987 1 14 42.56 142.85 102 6.5

4 1987 1 16 42.79 145.10 54 5.1

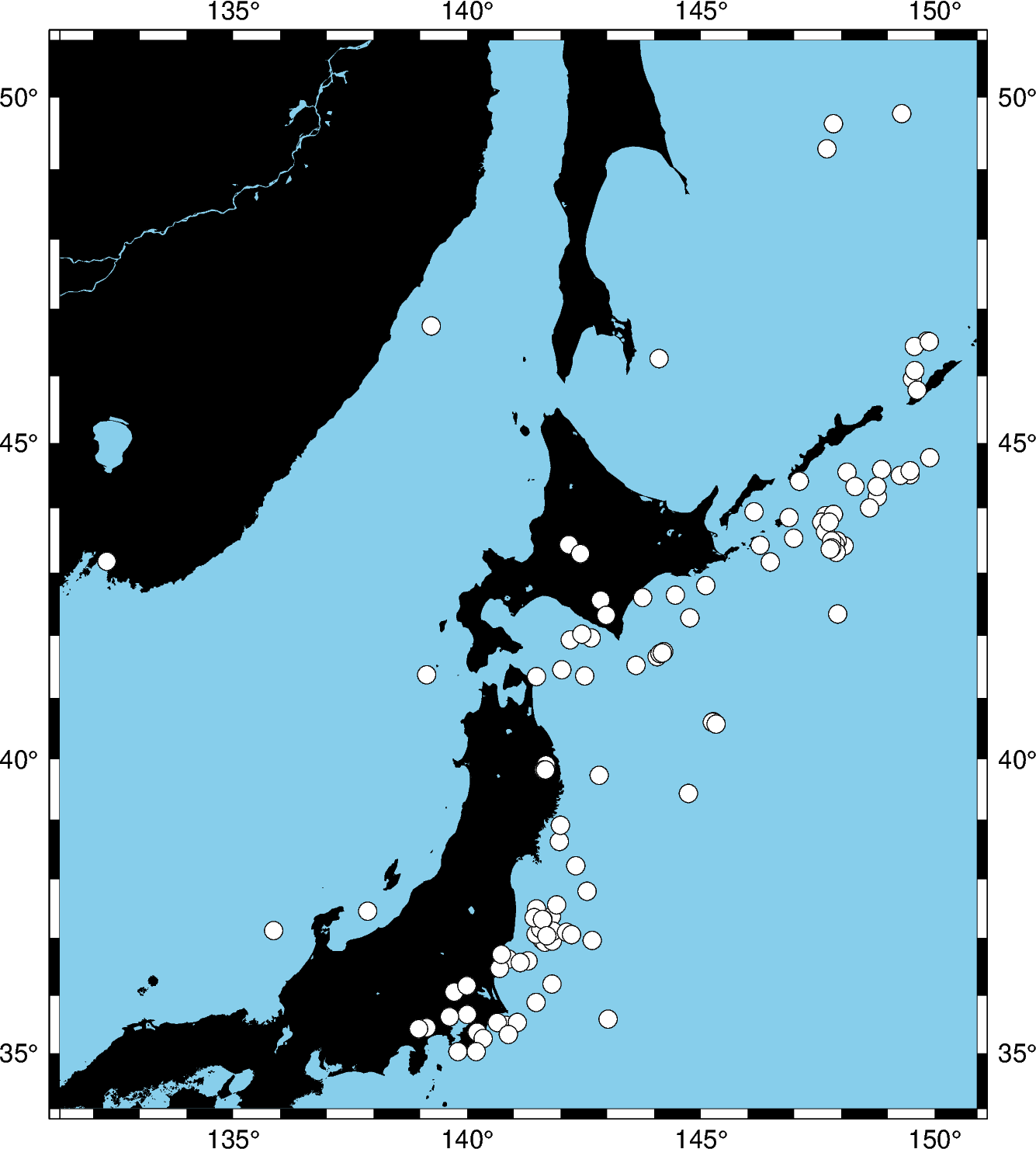

We’ll use the pygmt.Figure.plot method to plot circles on the earthquake epicenters.

fig = pygmt.Figure()

fig.basemap(region=region, projection="M15c", frame=True)

fig.coast(land="black", water="skyblue")

fig.plot(x=data.longitude, y=data.latitude, style="c0.3c", color="white", pen="black")

fig.show()

Out:

<IPython.core.display.Image object>

We used the style c0.3c which means “circles of 0.3 centimeter size”. The pen

parameter controls the outline of the symbols and the color parameter controls the fill.

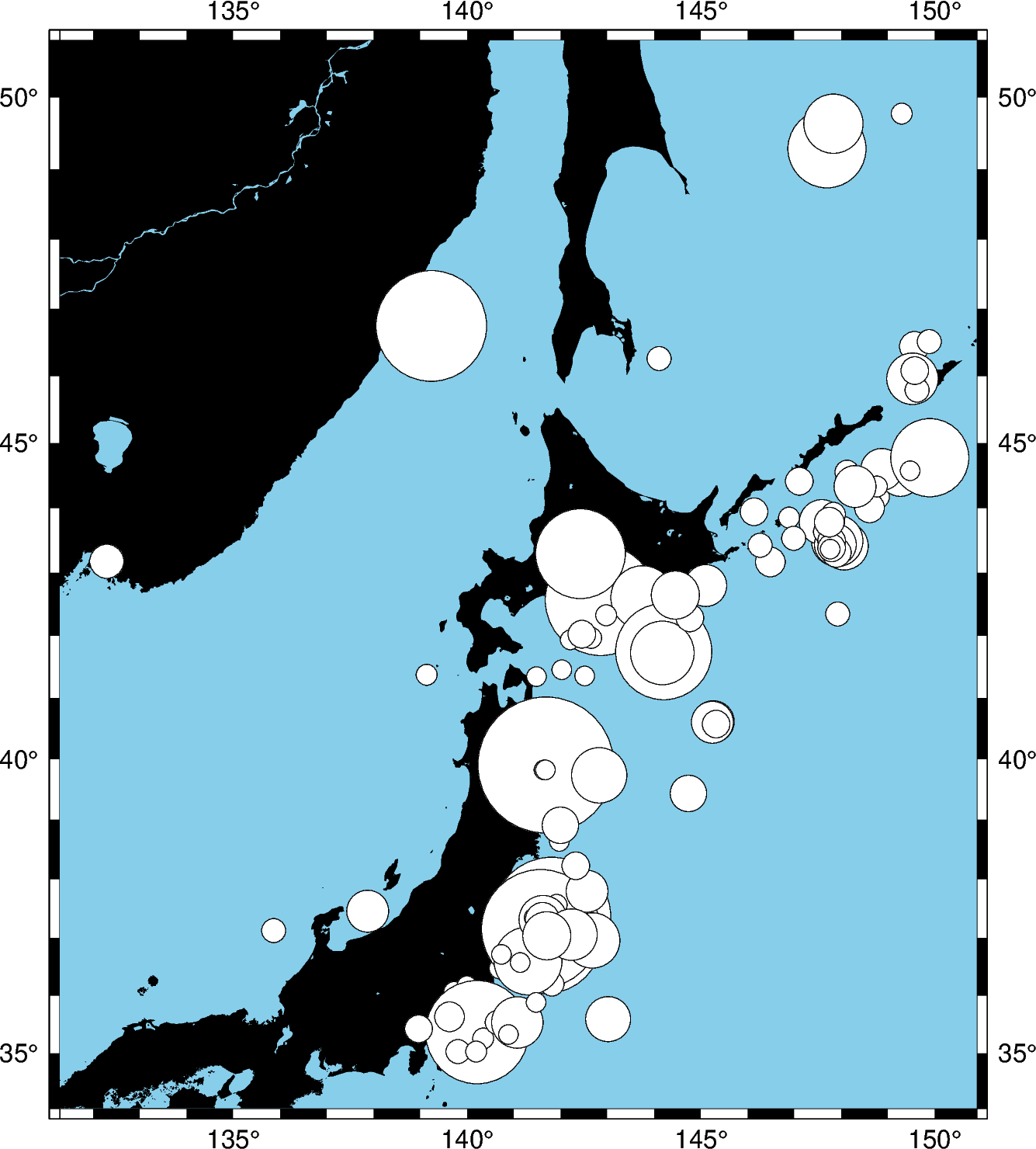

We can map the size of the circles to the earthquake magnitude by passing an array to

the sizes parameter. Because the magnitude is on a logarithmic scale, it helps to

show the differences by scaling the values using a power law.

fig = pygmt.Figure()

fig.basemap(region=region, projection="M15c", frame=True)

fig.coast(land="black", water="skyblue")

fig.plot(

x=data.longitude,

y=data.latitude,

sizes=0.02 * (2 ** data.magnitude),

style="cc",

color="white",

pen="black",

)

fig.show()

Out:

<IPython.core.display.Image object>

Notice that we didn’t include the size in the style parameter this time, just the

symbol c (circles) and the unit c (centimeter). So in this case, the sizes

will be interpreted as being in centimeters.

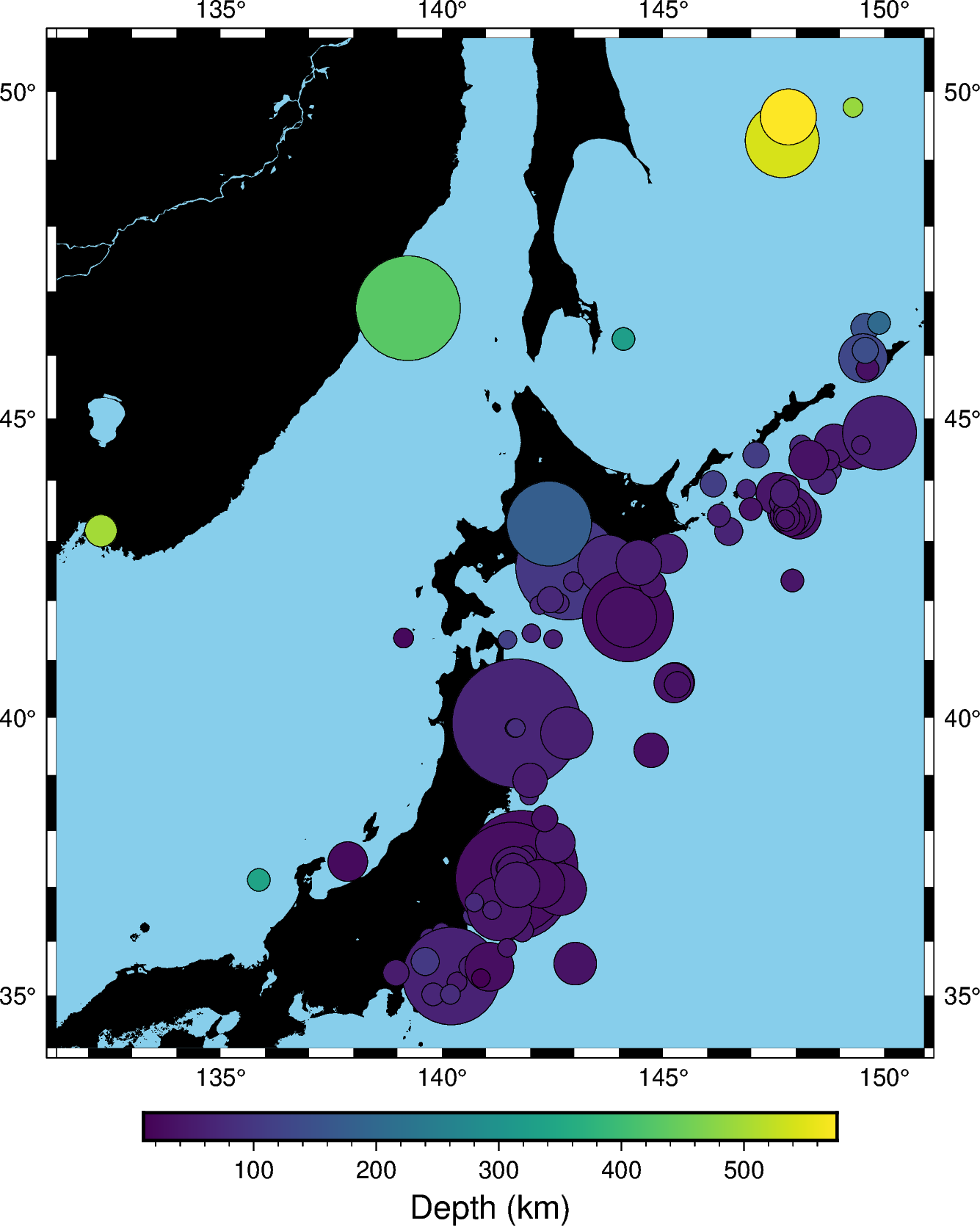

We can also map the colors of the markers to the depths by passing an array to the

color parameter and providing a colormap name (cmap). We can even use the new

matplotlib colormap “viridis”. Here, we first create a continuous colormap

ranging from the minimum depth to the maximum depth of the earthquakes

using pygmt.makecpt, then set cmap=True in pygmt.Figure.plot

to use the colormap. At the end of the plot, we also plot a colorbar showing

the colormap used in the plot.

fig = pygmt.Figure()

fig.basemap(region=region, projection="M15c", frame=True)

fig.coast(land="black", water="skyblue")

pygmt.makecpt(cmap="viridis", series=[data.depth_km.min(), data.depth_km.max()])

fig.plot(

x=data.longitude,

y=data.latitude,

sizes=0.02 * 2 ** data.magnitude,

color=data.depth_km,

cmap=True,

style="cc",

pen="black",

)

fig.colorbar(frame='af+l"Depth (km)"')

fig.show()

Out:

<IPython.core.display.Image object>

Total running time of the script: ( 0 minutes 5.235 seconds)